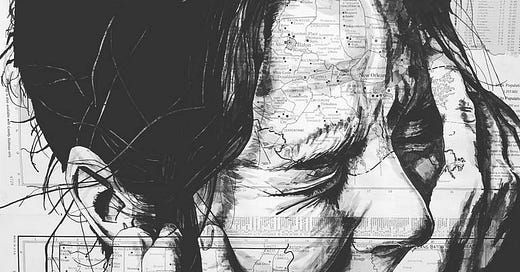

When the Body Is Finally Believed

From 1789 to 2089: A Pain Patient’s Journey Through Time, Gatekeeping, and the Future of Care | Introduction to the series: “The Pain Traveler.”

What does it mean to suffer in a time that doesn’t believe your pain?

As a man in the 21st century with chronic thoracic and rib pain—undiagnosed, undertreated, and widely misunderstood—I have often asked myself: Would it have been any different had I lived in another time? Or will it take another century before people like me are finally seen?

To answer that, I imagined what my life might have looked like if I had been born in 1789, the year of revolutions and rudimentary medicine—and then imagined it again in 2089, a century into the future.

1789: The Age of Ignorance and Isolation

In 1789, pain was either obvious or invisible. Unless a limb was severed, blackened with infection, or bent grotesquely, medicine had little to say. The language of suffering was spiritual or moral. Pain without external cause was often attributed to melancholy, hysteria, or moral weakness.

There were no MRIs. No mechanistic models of central sensitization. No anatomical understanding of costovertebral joint dysfunction or autonomic dysregulation.

Had I presented with my current condition—spasms in the thoracolumbar region, persistent rib pain, biomechanical dysfunction—I would likely have been:

Dismissed as mad,

Bled or purged to “balance humors,”

Or condemned to silent suffering, institutionalization, or religious repentance.

Pain was personal—but it was also political. To suffer in silence was the patient’s burden. To act without evidence was the physician’s prerogative.

2025: The Age of Knowledge Without Compassion

We are now centuries beyond humoral theory. We have pain science. We have sophisticated imaging. We understand neural plasticity, the role of glial inflammation, the biomechanics of the rib cage, and how central pain amplification works.

But what we don’t have is access.

My own clinical experience is a case study in modern system failure. Despite multiple referrals, repeat imaging, documented therapy failure, and significant loss of function, I am still being:

Denied interventional care,

Sent back to ineffective conservative measures,

Or gaslit by providers who would rather refer me away than admit uncertainty.

Why? Because the system is built not around the individual, but around protocols, liability aversion, and insurance approval pathways.

This is the era of protocolized healthcare—a model where care is algorithmic, standardized, and designed around cost control and legal defensibility, not patient-centered nuance. Where guidelines become shackles, and “first-line treatments” become recycled prescriptions for failure.

Part of this failure lies in how modern pain medicine has shifted from a biomechanical to a biopsychosocial model, often without balance or discernment. The biomechanical model once emphasized structure, instability, and movement dysfunction. But today, it is frequently abandoned or dismissed in favor of the biopsychosocial model, which—while valuable in theory—can be misapplied to pathologize the patient rather than treat the body. When used improperly, it shifts the blame inward: implying that pain persists due to fear, deconditioning, or catastrophizing, rather than acknowledging unresolved biomechanical dysfunction, nerve sensitization, or joint instability. In my case, this skewed framework has been used to rationalize inaction, recycle failed therapies, and justify clinical avoidance.

Beneath all this lies a deeper assumption—primitive, but persistent:

“If we can’t see it, we don’t treat it.”

In modern terms, this means: if your MRI is “unremarkable,” if there’s no acute fracture or tumor, then your pain becomes suspect. The body is judged only by what machines can visualize. Subtle dysfunctions—mechanical misalignments, joint fixations, altered load transfer, neuromuscular bracing—are dismissed because they don’t glow on a screen.

This is the modern blindness: a system that trusts images more than people, protocols more than presentation, and guidelines more than clinical reasoning.

Yet radiographic silence does not equal clinical absence. In sound medicine, it is the patient’s body—not the scan—that speaks first. Clinical evidence must take precedence over radiographic confirmation when the signs are unmistakable, persistent, and functionally disabling.

This is the essence of humane care: treating the patient, not the labs. When the clinical picture is compelling, physicians must act—not wait for permission from pixels or insurance tables.

And perhaps at the heart of this failure lies medicine’s overreliance on the quantitative at the expense of the qualitative—numbers over narratives, metrics over meaning. Care becomes task-oriented rather than patient-centered. The body is measured, not experienced. But pain is not just a data point; it is a lived ordeal that defies capture in checkboxes or lab panels. Until we restore medicine’s qualitative soul—its listening, its witnessing, its responsiveness—patients like me will remain statistical anomalies, not human beings in distress.

2089: The Age of Precision and Patient Sovereignty

Now imagine the year 2089.

Pain is no longer measured by scales or self-report alone. Instead, we can directly image neural pain networks, track spinal instability in motion, and model the body’s functional breakdown in real time.

The moment my body presents signs of dysfunction—autonomic flare, segmental rigidity, rib malposition—intervention begins. No waiting. No preauthorization. No “prove it again” gauntlet.

In this future:

Diagnostic models are biomimetic, not bureaucratic.

Every patient has a bio-integrated AI advocate that audits refusals and escalates denials for independent review.

Gatekeeping is criminalized, classified as medical negligence when indicated treatments are denied without cause.

A patient’s digital case file includes real-time data from wearables, biomechanical sensors, and personalized genetic overlays, making diagnosis precise and individualized.

Most importantly: belief is automated.

No longer a social negotiation, but a physiological certainty.

The Philosophy of Pain and Personhood

Philosophically, pain is not just a biological event—it is an existential condition. It collapses time, shatters identity, and reduces autonomy to dependence. Pain forces the question: Is my suffering real if no one validates it? And more chillingly: Does my body count if the system refuses to see it?

In this light, pain becomes a political phenomenon. It reveals the gap between embodiment and recognition, between being in pain and being treated for it. Medicine, when reduced to statistics and scan reports, becomes blind to the person in front of it. It begins to treat data points, not souls.

To be in pain and disbelieved is to experience a double injury: one of the flesh, and one of dignity. It is a kind of exile from the human commons. What patients like me need is not just relief—but acknowledgment, moral seriousness, and epistemic justice.

True medicine begins not with tests or protocols, but with bearing witness. It must return to its roots in care, relationship, and presence. Without this, even the most advanced tools will remain blunt in the face of suffering.

Conclusion: The Real Revolution

History will not remember the MRIs. It will not remember the guidelines. It will remember who was believed—and who was left behind.

The real revolution in medicine will not come from machines or molecules.

It will come from returning to the body.

From learning to trust what it says.

And from treating pain not just as a problem to solve—but as a life to serve.